Malala, Empire, the Algorithm and What We Get Wrong About Liberation

Divide and conquer has never been easier.

The Empire doesn’t need bombs and spies any more. The algorithm is now the Empire’s favorite tool to divide and conquer. It flattens nuance, replaces discernment with rage, and ultimately distracts from real Empire building.

And it often does this by using the oldest tactic in Empire’s playbook: weaponizing a woman’s contradictions and choices.

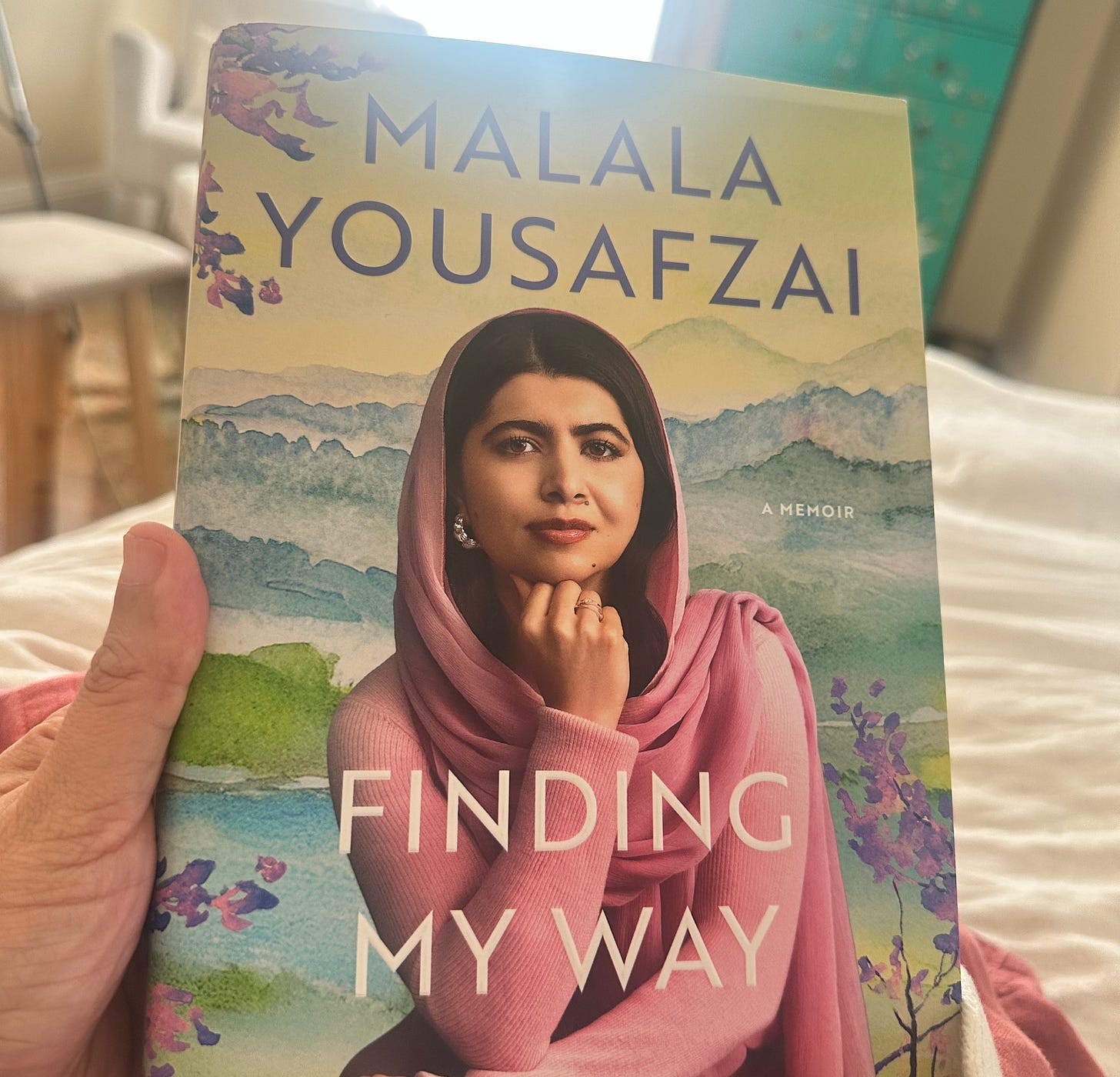

Two weeks ago, 28-year old Malala Yousafzai began a media tour in the UK and US for her new memoir, Finding My Way.

Immediately tabloid-esque, cringeworthy viral headlines dominated our feeds with words like “sex bomb” and “bong,” while describing the memoir written by the only Pakistani and youngest human ever to win a Nobel Peace Prize.

She appeared on all the top Western TV shows and with the most popular brown influencers. Many of whom give her saint-like status.

But Malala is no saint to the majority of Pakistanis. And the book tour seemed to be built for Western audiences and the imperial gaze.

While her intention was clear from the book’s name, Finding My Way, Pakistan’s left and right were united in their disdain for her choices of not choosing what they wanted her to be or what they deem the moral choice to be.

For the right who hate her, she’s been a “drama, a CIA agent, or a Western stooge” ever since she got a mic, way before she was shot by the Taliban at 15.

Those on the left, who used to defend her, also seemed to have stepped away and call her out for building her own empire. They want her to start being anti-Empire, put oppressed communities at the center, and use her power to speak up for Palestine the way Greta Thunberg does.

But does she really have the power to be anti-Empire? The single largest individual donation Malala Fund’s has ever received was $25 million from Airbnb and Samara co-founder Joe Gebbia. And by erasing her unique Taliban-Swat backstory, controlling parenting context, rural Pushtun cultural expectations, or shooting and disfigurement PTSD – aren’t we too expecting her to be a saint with no strings or trauma?

While I didn’t feel rage towards Malala about the book branding, I felt deep disappointment. A few dozen DMs later, many asking me to compare Swedish activist Greta to Malala, I made a quick video on IG. It wasn’t a well structured argument that tackled all the disinfo and misinfo around Malala. My initial intention was to post it in my stories, and just address how odd that comparison is. But I posted it on my feed and allowed the algorithm to stretch it and distort it.

It got 150,000 views, 5000 likes and hundreds of comments that ranged from thank you to showing me this perspective, to hate, to misinformation, to making Malala–and by extension me–a punching bag for all their distortions and projections.

The Book as a Mirror

As I tried to deconstruct the reactions to the video to write this essay, I realized I needed to read her book. I couldn’t talk about her without actually reading the primary source. As soon as I read the first page, I knew her book was her response to everyone telling her who she should be - from the raging Pakistanis at keyboards, to her parents, to Western folks who had made her a saint.

Here’s the first page of her book.

l’ll never know who I was supposed to be. Maybe everyone feels that way, curious about the invisible crossroads in their lives, the wrong turns and chance encounters that change everything. But I am haunted by it, the gulf between how I imagined my life and what it became. I can’t escape the feeling that a giant hand plucked me out of one story and dropped me into an entirely new one. On a mild October afternoon, a bullet changed the trajectory of my life, cutting me off from my home, my friends, and everything I loved, spinning me out into an unfamiliar world. At fifteen years old, I hadn’t had time to figure out who I wanted to be when, suddenly, everyone wanted to tell me who I was. An inspiration, a hero, an activist. But also a wallflower, a punching bag, a paycheck. To my parents, I was an obedient daughter. To my friends, a good listener. When I was alone, I unraveled —because the hardest thing to be was myself.

Malala’s book is about a girl finding her way. And after reading about her journey, which by the way doesn’t even mention sex bomb or bong until halfway in, I feel embarrassed that I felt deep disappointment when the algorithm was just playing me.

Most of her book is about how loneliness, expectations, and trauma has been her constant companion since she was shot, and how she almost failed out of Oxford.

I took my seat and waited for the test to begin, said a little prayer, and hoped I wouldn’t bomb too badly. Whatever marks I received at the end of the term didn’t matter, I told myself. I had already passed my own test, the one I’d set at the start of the year: to find a group of friends who understood me. At Oxford, I could be myself, free from the expectations of the outside world. My friends didn’t care about my thoughts on global events or what I wore. They accepted my quirks and contradictions, my bad days and chronic tardiness.

She later writes, “I had passed my first year at university, but I wouldn’t continue to scrape by as classes got more difficult,” her advisor warned in a letter.

The letter continued, itemizing my sins: essays submitted after the deadline, failure to complete my weekly reading assignments, and skipped tutorial sessions meant to help struggling students catch up before exams. You did not appear to be doing sufficient independent work. I didn’t care where I ranked among the other students, but Lara’s line about my “passionate commitment to education” stung. Would people think I was a fraud or a hypocrite for giving speeches about the importance of girls going to school if they saw my prelim exam marks? My critics would love it: the world’s most famous education advocate, the poster girl for bookish children and perennial teacher’s pet, unmasked as a college delinquent.

By writing this book, Malala has stubbornly stepped out of forced sainthood and told us she’s trying to learn to exercise her own choices, and it may be messy, but this is exactly why she advocates for girls education, so girls can make their own choices, irrespective of the stones thrown at them.

We all live in the Empire’s Glass Houses

In 1979, at the Second Sex Conference in New York, Audre Lorde said, “For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” Lorde was arguing that true liberation cannot be achieved using patriarchal frameworks.

Since the genocide started, her wise words have been repeated again and again to refer to Western imperialism. And I’ve seen them used for Malala, referring to her and her Malala Fund as a master’s tool to offer cover to imperial crimes. But these past two weeks, I’ve seen most Pakistanis ask that she use those very tools to take on imperialism. My brain short-circuited at this logic.

While most know Lorde’s first line. Few read the rest.

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. Racism and homophobia are real conditions of all our lives in this place and time. I urge each one of us here to reach down into that deep place of knowledge inside herself and touch that terror and loathing of any difference that lives here. See whose face it wears. Then the personal as the political can begin to illuminate all our choices.”

Few consider the work she describes: reaching down, confronting the hate and loathing within ourselves. That is the real labor of liberation. Only before we do that can we confront Empire. As I read through Malala’s book, it became clear she was digging down in herself to understand the loathing and fear in herself. A girl who became the youngest person to win the Nobel Peace Prize, but wasn’t allowed to have a lock on her bedroom door or choose the clothes she wore, or who wanted the ground to swallow her when her mom screamed “don’t touch” to Prince Harry as he was posing for a picture with her. A girl who had to get permission from the Pakistan military to even visit her home or family. It took her 5 years to be allowed a few hours in Mingora and 4 days in Pakistan. Once she was in a room with her whole extended family and community, her whole world before she was shot, her Uncle said with a mic in his hand, “Look at her face-she has sacrificed her beauty to give a good image to Pashtuns and Pakistan.”

Pakistanis love and hate to claim Malala as her own, but they refuse to acknowledge how different her backstory is as a rural Pashtun woman. In her book she writes about hearing her now husband’s life in Lahore:

It always made my head spin to hear stories like these from those who grew up around the same time as me, in the same country. When I was a child in Mingora, there were no Pizza Hut dates or punk records or online chats. I’d never imagined that the teenage world was so different just a few hundred miles away in Lahore.

When she arrived in Birmingham shot at 15, she’d only read about a dozen books. Even today most of the cousins she grew up with were married at 15 unable to get an education. Her fight is singularly focused on girls like that in her mother’s hometown Swat’s Shangla, but also in Africa, and Palestine.

The truth is we all use Western tools — iPhones, universities, social media platforms — to rail against the Empire. We all live in the Empire’s glass houses but throw stones at others we think are living in the Empire’s palaces.

We may say we are progressives and feminists but put unreal expectations on one woman to take on Empire and rail at her exercising her choice not to.

As I tried to tackle the disinformation in the comments, I became curious why so many young Pakistanis who identify as “woke” or “progressive” or “feminist” Pakistanis were so angry at Malala. It boiled down to Gaza. They were angry she didn’t use “genocide” as a qualifier until two months ago. They expected her to stand up to Western imperialism. The girl who could barely stand up to her parents, whose whole global identity was formed in the context of Western imperialism. The girls whose parents focused more on her getting over a dozen surgeries for facial paralysis, but dismissed her PTSD. Many didn’t know her power is within the confines of Western imperialism and what was expected of her. Saying “genocide” any sooner, would erase her power to send money to Palestinians. Something she’s been doing since 2014.

On Pakistan’s Complicity on Palestine

Malala’s book tour seemed to be the icing on the upside down cake we’ve been living in the last two years. It was the week of the controversial Trump and Muslim country orchestrated Gaza “peace” deal.

Like many Pakistanis, I felt nauseous seeing headlines that put our government and military front and center of a “peace deal” that celebrated Trump as a peacemaker, betrayed Palestinians, and reversed decades of Pakistan’s foreign policy — a policy rooted in refusing to recognize Israel until a fully independent Palestinian state is established as East Jerusalem as Palestine’s capital. Pakistani passport holders know this well; their passports literally state they’re not valid for travel to Israel.

Israel came into being shortly after Pakistan. From the start, Pakistan’s founder, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, viewed Israel as an illegitimate creation and voted against the UN Partition Plan for Palestine in 1947. That position — no recognition without an independent Palestinian state — has held firm across governments, even after Israel’s peace agreements with Egypt (1978), the PLO (1993), and Jordan (1994).

Yet the week Malala’s book came out Pakistan’s puppet prime minister reaffirmed his country’s stance that Trump should get the Nobel Peace Prize, and Trump reaffirmed his love for Pakistan’s actual ruler, Field Marshall Asim Muneer.

He’s the second self-crowned Field Marshall in Pakistan’s history. The first one, Ayub Khan, was also loved by the White House. He was the one who closed the door on the Soviets and put Pakistan on the path of becoming a Western imperial proxy in South Asia. That position held strong for decades, until India started moving away from the Soviets to the US in the 90s. Pakistan soon became America’s disposable ally. (I made a 3-part documentary series on this 16 years ago).

Most Pakistanis were fuming at Pakistan’s U-turn. But online Pakistanis don’t rage about their military or puppet government anymore. When they do, the internet gets cut off, families get harassed or picked up, their businesses and homes get raided. It’s been three years of this cycle.

So when Malala’s book dropped, most Pakistanis were already silently raging at their Western imperialist government, she became the punching bag they could safely direct their attention to.

I want to address the biggest ones that showed up in the comments on my video.

The Biggest Distortions of Malala

She’s a puppet of Western imperialism

Yes, we all are. If you use an iPhone, order on Amazon, pay taxes in a Western county or a rent seeking state like Pakistan, you are also a puppet of Western imperialism.

She’s complicit in genocide.

Yes, the way we all are.

She’s been silent on genocide.

Distortion. Malala didn’t use the word genocide until two months ago, once the term was broadly used even by Western governments. This is likely because the language she uses has an impact on the schools and girls her fund supports. Also pissing off the Israeli government is one way to cut off aid to the families you are supporting. This is the world order frame in which she works.

That said, I’m going to share the exact language she used to refer to Gaza in 2021, captured in Pakistani American journalist Mariya Karimjee’s excellent NPR podcast earlier this month.

I want to express my solidarity with Palestinian people. After decades of oppression against Palestinians we cannot deny the asymmetry of power and the brutality from Israeli airstrikes on women and children in Gaza to stunt grenades targeting worshippers in Al Aqsa.

Malala has done nothing for Palestinians.

False. Malala condemned Israel’s assault on Gaza in 2014, donating $50,000 to children there. By 2021, her foundation worked with UNRWA to support girls’ education. Since 2023, the Malala Fund pledged $700,000 for Palestinian relief; she also personally donated $200,000.

Malala went to Oxford, she should speak up against genocide.

Huh? This one I found quite odd. But after reading her book, I realized how odd it was. Malala was failing through most of Oxford, because of unaddressed PTSD, her Malala Fund commitments, and all her speaking gigs, which not only paid for her family’s expenses but multiple others her family had taken on. She felt like an imposter advocating for girls’ education. Only after her advisor sent a strict note home telling her parents she’d fail out of Oxford if they didn’t stop her from working, was she able to study.

Malala is not an impoverished Swati girl anymore, she’s elite

True. Her new class mobility has given her opportunity towards and insulation from many things — but opportunity and insulation, without stepping into your agency, isn’t liberation. It’s another form of exile if you haven’t learnt who you are or what you stand for. The book makes it clear she’s trying to find her way to agency and liberation.

She hasn’t used her power to end the suffering of Palestinians

Distortion. She doesn’t have that power, the UN doesn’t even have it. French leader Macron doesn’t even have it. But she does have power to raise money for schools and girls. And that’s what she’s been focused on.

Malala made a play with war criminal Hillary Clinton

Distortion. Much of the hate around her collaborating with Hillary Clinton on a production of the suffragettes isn’t exactly true. Executive producers are constantly added to projects, without others knowing or giving consent, and that’s how Malala says that went down. That said, in her book, Malala says when the Taliban took over in Afghanistan in 2021, she was coming out of her 12th surgery to address her facial paralysis that plagued her parents so much, and she spent her recovery trying to rescue her partners out of Afghanistan. She mentions Hillary as one of the few women who helped. Sharing an excerpt from her book here:

With millions of people trying to leave through a single operating airport, it felt like we needed a miracle. I requested calls and sent urgent emails to presidents and prime ministers in various countries to ask for help, nervously fiddling with the stitches around my ear while I waited for an answer. For years, I’d smiled in pictures with these leaders, shaken their hands, and stood next to them at podiums-but not one of them picked up the phone or replied to my messages now. To the men who ran the world, I was just a photo op, not someone worthy of their time and attention, even when I needed it most. Women, on the other hand, responded immediately, answering my calls and jumping into action as soon as we hung up.

Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg, former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and their teams helped our Afghan partners get seats on the planes leaving Kabul. Lolwah Al-Khater, the assistant foreign minister of Qatar, allowed them to enter the country without paperwork, or even passports in some cases, and provided housing until we could sort out their relocation plans. Lisa Cheskes and Elizabeth Snow, resettlement managers in the Canadian government, guided us through the process of securing refugee visas. I may not personally agree with every opinion these women hold or every decision they made as leaders- but I will forever be grateful to them for helping save so many lives.With their support, Malala Fund helped 263 people evacuate Afghanistan.

While I understand the rage towards Hillary Clinton, I don’t understand why there is more rage towards her than Obama or Trump. After all Hillary Clinton was the one who actually lifted the veil for how fucked up foreign policy was for Pakistanis by giving her groundbreaking congressional testimony in 2009.

Our policy toward Pakistan over the last 30 years has been incoherent. I don’t know any other word to use. We came in in the ‘80s and helped to build up the Mujahideen to take on the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. The Pakistanis were our partners in that. Their security service and their military were encouraged and funded by the United States to create the Mujahideen in order to go after the Soviet invasion and occupation. The Soviet Union fell in 1989, and we basically said, thank you very much; we had all kinds of problems in terms of sanctions being imposed on the Pakistanis. Their democracy was not secure and was constantly at risk of and often being overtaken by the military, which stepped in when it appeared that democracy could not work. And so I think that when we ask that question it is fair to apportion responsibility to the Pakistanis, but it’s also fair to ask ourselves what have we done and how have we done it over all of these years, and what role do we play in the situation that the Pakistanis currently confront.

The algorithm doesn’t care for truth. It thrives on certainty, outrage, and spectacle. Context is flattened. Complexity is erased. Rage is rewarded.

Malala’s story is layered.

As much as people or the algorithm try to flatten her experience or situation, Malala’s story is layered.

The book’s rollout coincides with her launching a new for-profit sports fund for women with her husband Asser Malik, who previously worked in Pakistan’s private cricket leagues. This is her second fund, following the non profit Malala Fund she co-founded with her father and Shiza Shahid, the fresh Stanford graduate who quit her job with McKinsey, while Malala was undergoing multiple facial and skull surgeries at 15. Shahid was the face of the Malala Fund in its initial years, she was named TIME’s 30 Under 30 People Changing the World and Forbes’ 30 Under 30, making her a popular speaker at corporate retreats. Shahid’s name has been erased from the Malala Fund’s website now, and she isn’t mentioned once in her new book, but Shahid’s bio and speaker profile still carries that credit on multiple websites and lists her speaker fees at $24,000-44,000. She now runs the viral cooking pan company Our Place, which has Selena Gomez as its ambassador.

Soon after getting married, Malala also dipped her toes into executive producing for Joyland, (post production), a Pakistani film about trans love that won at Cannes, producing series for Apple and a play on the suffragettes with Hillary listed in the credits that upset so many Pakistanis.

This phase of her life — entering Hollywood, redefining her activism, and seeking her own voice — looks like a rebrand. The life her father chose for her isn’t the one she wants anymore.

For years, when people asked my dad about how he raised me, he’d always replied, “Don’t ask what I did. Ask what I did not do.I did not clip her wings.” He often spoke of me as a bird, but sometimes I felt more like a kite-flying high when it served him, pulled back to earth by a string when it did not. (Page 249)

She is no longer just the Pashtun girl from Swat Valley who was shot in the face by the Taliban at fifteen. She is also a woman finding her own way — negotiating trauma, parental expectations, global fame, and the politics of Empire.

Before Malala got shot

Flashback to 2009, I was a senior duty editor for DawnNews, which means I was running the news shift. Our reporter Irfan Ashraf who covered Swat was on leave, and our bureau chief from Peshawar sent an interview with a child named Malala from Swat, calling for the military to intervene as the Taliban had taken control of large parts of Swat and were banning girls schools or women’s movement. I was immediately concerned about parental consent and her father Ziauddin Yousafzai not only sent it, he was pleading for it to go on air. While I was thinking over what to do, pixelate her face and remove other attributions that could reveal her identity for her safety, our Swat reporter called. He asked me to immediately delete the file from our servers. He explained that she was the anonymous blogger Gul Makai who was writing on BBC Urdu and the Taliban were after. He said they’ll immediately know it’s her and her life will be in danger. He said he and others had all advised Ziauddin against this, but Ziauddin had gone behind his back asking the Peshawar bureau chief to come down and cover it while he was away.

So we deleted the video and that was that. But her father really wanted her on TV, and two weeks later Hamid Mir came down to Swat and interviewed her. This 12 year old was made the face of Pakistan’s military fight against the Taliban.

A year later, my colleague Adam Ellick at the New York Times wanted to make a film on the military’s fight against the Taliban in Swat. I connected the team with Irfan Ashraf, confident that he would meet the sensitivity and ethical needs for the story. But Ellick found Malala’s story most compelling and he ended up making her the central character with Irfan Ashraf as the Associate Director on the team. That film is what made Malala famous. It’s what caught Stanford student Shiza Shahid’s eye and made her reach out to Malala’s dad. After Malala was shot Shiza quit her job at Mc Kinsey in Dubai and flew over to help Malala’s family manage PR and the funds that were pouring in to help Malala. Madonna performed with Malala on her backside. Celebrities everywhere were praying for her while she was in surgery while Shiza and Malala’s dad got together to figure out the Malala Fund.

Malala’s early life was framed by the pressures of saving Swat, surviving trauma, and meeting the expectations of Empire. She was twelve, shot at fifteen, and by eighteen, the world had claimed her story as its own. In 2014, I spoke to Irfan about this in a podcast I hosted back then, sharing it here:

Malala’s rebrand and what about her agency?

Fast forward: Malala is 28, an Oxford graduate, married, and launching Recess Capital, a for-profit sports fund for women with her husband. She’s producing films, series, and plays. Finding My Way is a manifesto of self-discovery within Empire. She is negotiating autonomy after a lifetime of curated expectations — from her father, from the world, from Pakistan.

What struck me in her book was how aggressive and constant her surgeries have been since she was shot. Her trauma isn’t just from getting shot in the face and losing hearing and facial asymmetry, it’s from the constant focus of her family on fixing that and not acknowledging the very real mental trauma she faced. This is from 10 years after she was shot.

On our current visit, they would remove part of my upper left thigh and deposit it inside my cheek. With any luck, the nerve from my calf would attach to the tissue from my thigh and begin sending signals to the muscles in my face. Initially I did not want to do the cross-facial nerve graft; it meant spending weeks of time in hospitals and recovery rooms for three consecutive summers. My parents, however, kept pushing for a cure. They wanted to erase the memory of seeing me for the first time in the Birmingham hospital with sunken eyes and a paralyzed mouth-to silence the comments, from relatives and online trolls, about how pretty I “used to be” before the shooting. My parents and the doctors had convinced me it would be worth the effort in the end, so off we went to Boston.

Her choices unsettle us because we expect her to perform heroism perpetually. We flatten her story, erase complexity, and rage at her failures of agency.

Agency under Empire or patriarchy doesn’t vanish — it distorts. Choices for her were made within threat matrices, funding conditions, and family expectations.

Meanwhile she’s a terrified woman who gets panic attacks, has PTSD, often thinks she’s failing everyone around her on metrics she didn’t choose for herself. Half of her book is about her falling in love with her now husband Asser and feeling terrified at stepping into her own agency by choosing marriage because what if the first time she’s stepping into her agency, she makes the wrong choice? Malala didn’t know much about choice or family emotional support, or stepping into her own agency even as a 25 year old.

Which is why I find the Greta and Malala comparisons so odd.

Greta and Malala

When Greta was 11, her mental health started to deteriorate. “She cried at night when she should have been sleeping. She cried on her way to school. She cried in her classes and during her breaks, and the teachers called home almost every day. She was slowly disappearing into some kind of darkness and little by little, bit by bit, she seemed to stop functioning. She stopped playing the piano. She stopped laughing. She stopped talking. And she stopped eating,” her mother shares in a book about Greta.

Eventually Greta was taken to a doctor after she lost 10 kgs in 2 months.

She was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome (a form of high-functioning autism) and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). Over time, with treatment, her mood began to lift, she would eat selectively at home, and she started at a new school.

One day after school she told her family, “I want to start eating again” to their immense relief. The lightbulb moment came when Greta watched a film in class about ocean pollution and the ‘island of plastic’ in the South Pacific.

This marked the start of a new chapter for Greta, who was then only 15. After a string of heat waves and wildfires in Sweden, she’d made the decision to miss school to sit outside Swedish Parliament every day until the general election. Greta held a sign that translated as ‘School Strike for Climate’. Her key demand was that the Swedish Government reduce carbon emissions as per the Paris Agreement. Her father recalls, “On day three someone came along and gave her Pad Thai (vegan) and she ate it… I cannot believe or explain what that meant to us, but it was just like she changed and she could do things she could never have done before.” Because of OCD, Greta would usually only eat at home until this point.

That day launched her global Fridays For Future (FFF) movement, which went on to engage over 13,000,000 strikers in 7500 cities across the world. Six years later, at the COP24 conference in Poland, we saw Greta announce boldly, ‘I don’t care about being popular. I care about climate justice’ - which sums up her approach, her support, her backstory, and her agency perfectly.

Malala, on the other hand, was dressing to meet her mothers approval and living out her father’s activist dream until she got married. In her book, she explains how she was failing college to do speaking engagements to pay for the expenses her parents had taken on for multiple families and how her needs for mental health support were dismissed for years by her parents.

Greta could skip school to protest with her family’s support. Malala was shot in the face for joining her father in defying the Taliban. They are not the same story — and we need to stop pretending they are.

Malala’s story reminds us that surviving the Empire as a child is messy. It requires self-reclamation. Greta’s story shows what a child with structural support, parental care, and freedom can do within Empire. Both stories demand attention — not comparison, not simplification, but reflection.

Anti-imperial work requires discernment & nuance.

True anti-imperial work requires reflection, empathy, and humility. I’m learning that dismantling Empire starts small — in the way I scroll, the way I speak, the way I refuse to flatten a woman into a symbol, even when the algorithm demands it. I’m trying to discern the power structures shaping the lives of those I critique.

Movement work needs to center people and not symbols. Repair begins when we stop flattening people into symbols — when we honor their humanity alongside their achievements and failures.

Repair begins when we see how quick we demand online performance from anyone in the spotlight, while ignoring our complicity in Empire offline.

I’ve been organizing in public schools here under Berkeley Families for Collective Liberation for about 2 years — defending teaching about Palestine, calling out censorship, and connecting it to Empire-building. The work is respectful, personal, and nuanced. It is unalgorithmic. When we build bridges and recruit one more family into anti-Empire work, we are calling people in, never calling out. Guilt and shame are not tools of recruitment in real life.

All of us in the movement are US taxpayers and complicit in Empire and genocide. Most people I organize with are home owners, I am not. Most dropped Amazon Prime a while ago. I couldn’t and didn’t. Some dropped Apple, I couldn’t and didn’t. Many are vegetarian or vegan. My chronic anemia ensures I’ll never be. Most have Palestine flags or posters, outside their house or on their car. I don’t for safety and surveillance reasons. Yet there is no judgment or discussion from any of them about my individual choices. We are all anti-Empire and show up the way we can, given our conditions, backstory, and our safety needs in real life.

We all live in glass houses in real life. Online we rage, scroll, post, and critique from inside them. Algorithms feed our outrage, reward certainty, and flatten nuance.

Liberation begins not with external demands of moral purity online, but with internal reckoning in our real life, the way Audre Lorde encouraged us to do. The way Malala so gently reckons with her parents’ context to understand the path they chose for her or why so many Pakistanis hate her for staying on that path. She isn’t raging, she is reckoning.

We must learn to hold contradictions, embrace complexity, and do the quiet, messy work of understanding our complicities. Only then can we support others, and ourselves, in finding a way that truly dismantles the Empire — from the inside out.

The book tells me Malala is on that journey, will she end up where we want her to? Will she step into her people power and help us dismantle Empire? I can’t say. But what I can say is the Empire is clever.

It no longer just rules territory. It rules narratives. It makes messy women into voodoo dolls. And if we are not vigilant, it will rule our imagination too. And we’ll find ourselves divided and conquered, pricking at its dolls instead of dismantling the Empire.

This was a long one. Thank you for reading until the end. Please like or drop a comment if my thoughts here made an impression on you. I’d be so grateful if you’d share parts of this essay on social media or in other ways with folks who you think might relate to it.

“The algorithm doesn’t care for truth. It thrives on certainty, outrage, and spectacle. Context is flattened. Complexity is erased. Rage is rewarded.” This is pure art sahar. I read with so much feeling, often tears rolling down. It’s speaks with terrifying beauty. Thank you for writing this piece with the grace and nuance it deserves

Beautifully written. I love how you go deep into Malal’s life and how shift your readers gaze to view her as a young girl rather than dehumanise her by putting her onto a pedestal and expecting her to be always right (whatever right is). Also as always this post also urges us to tread with kindness as most of your content does 🤍